An aerial photo of the heart of the

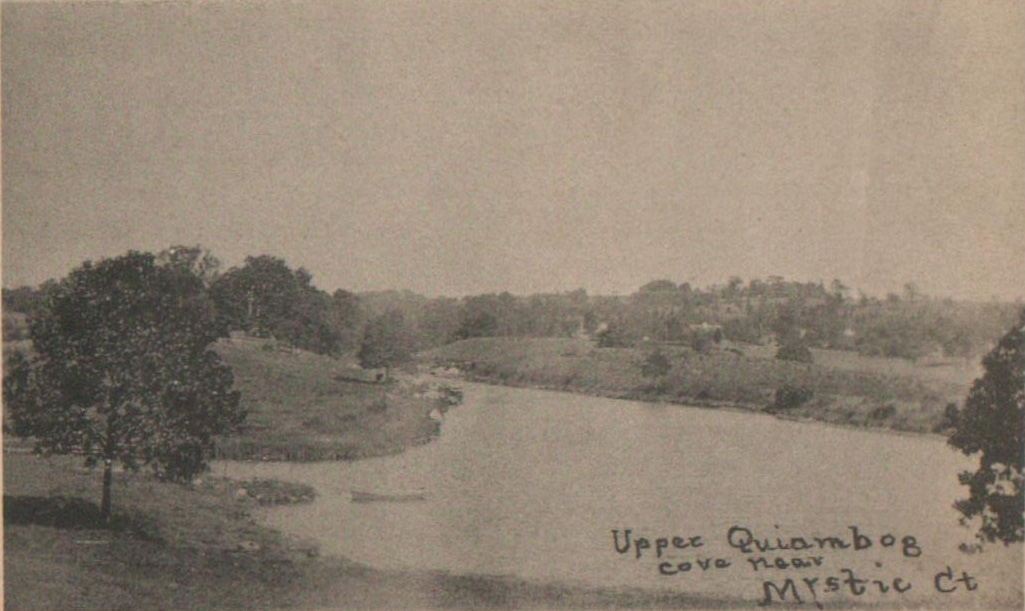

Quiambaug

valley, marked up with street names.

|

|

|

An aerial photo of the heart of the

Quiambaug |

A History of a Valley and its Two Ridges

Bryan A. Bentz

While I've written the first round of this set of pages, I'd like it to become a wider project, involving anyone who is interested. Indeed, eventually I hope this project takes on a life of its own, and continues for many years to come, even after I can no longer be involved.

Here is a link to the slideshow page (also available below) - here to give you a taste of some of the beauty and historical tidbits in the Valley.

|

More recent tidbits:

|

|

Table of Contents |

|

| 1. What It Is and Where It Is | 15. Latimer Point (separate web page) |

| 2. Geologic Prehistory | 16. Ongoing Events |

| 3. Human Prehistory | 17. Businesses Past & Present |

| 4. The 16th Century | 18. Historic Structures (separate web page) |

| 5. The 17th Century | 19. Murders |

| 6. The 18th Century | 20. Notable People |

| 7. The 19th Century | 21. Schools |

| 8. The 20th Century | 22. Roads & Railroads |

| 9. The 21st Century | 23. Mentions in Literature |

| 10. Hurricanes | 24. Current Status |

| 11. Museums, Preserves, and other Organizations | 25. Slide Show (separate web page) |

| 12. Special Locations | 26. Oral Histories |

| 13. Cemeteries (separate web page) | 27. Concluding Remarks |

| 14. Lord's Point (separate web page) | 28. References |

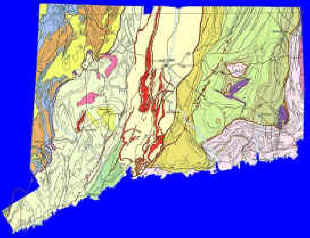

The Quiambaug Valley, and "village of Quiambaug", is in southeastern Connecticut, in the town of Stonington. It runs along a north/south axis, as is typical of the glacially-carved landscape of this part of New England.

When trying to describe any valley, it is difficult to define precise borders. Does the valley include the ridges that define it? How about the "outer" flanks of those ridges, that drain elsewhere? As far as a formal definition, there is a Quiambaug Fire District, a legal entity with the power to tax, which includes most of the southern part of the valley and the ridges on either side. However, the northern part of the valley is excluded.

At the south end of the eastern ridge is a point, broken up into two sections: Lord's Point and Wamphassuc Point, though both are really finger-like extensions of the same ridge. I doubt people on Lord's Point, which has its own history and community, would consider themselves as Quiambauggers, though geographically and geologically they are - they just don't look across the wide bay to Dodges or Andrews Islands, or Latimer Point, and see that as an extension of the Quiambaug Valley. Wamphassuc Point seems to have much more to do with the water on its eastern flank, Stonington Harbor, than it does with Quiambaug Cove, as residents face the obvious accessible water; yet the ridge giving Wamphassuc Point its high ground is clearly just a little further north the eastern ridge of the Valley. Similarly, on the western side of the Valley, the defining ridge breaks into different and distinct mini-ridges, forming Latimer Point, some islands, and the peninsula leading out to Mason's Island.

My eastern boundary, going as far as Stonington harbor, has one precedent - in the book "Steamboat Days", by Fred Erving Dayton (1925) one character describes the Borough of Stonington as "bounded on the north by the red barn, on the east by Wequetoquock, on the west by Quiambaug..."

I intend to take the largest reasonable region as my subject, simply because it will be more interesting to do so. A marked-up topographical map may be found here:

My choice is to cover the valley and the ridges on either side of it, a region about 4 miles "tall" (north/south) and between 1 and 2 miles wide (east/west); a total of about 6 square miles, from roughly Pequotsepos Brook in the west to Collins Cove in the east.

Why write about such a small specific place?

Some physical places dramatically affect the lives of people who live there, or shape the communities that form. Consider the Nile Valley, the rhythms of which drove the formation of ancient Egyptian culture. Other spots gave rise to communities with attributes that would shape their societies; for instance, locations where trade routes crossed, or with good harbors, would grow to be cities rich in both goods and ideas - Athens, Constantinople, Rome, London. Geography established the possibilities, and placed its stamp on the communities that would arise in those locations. To understand history one has to be sensitive to geography.

So why write about an obscure and quite small valley? It's too small by far, both in area and population, to have anything like a unique or identifiable culture, or to give rise to any sort of new valuable viewpoint. It is historically insignificant by pretty much any measure. In this age of a mobile population which with few exceptions doesn't work the land or the sea, it's quite possible that there are residents who aren't even aware they're even in a valley, much less what attributes it might have.

And yet I think it does have an impact, though it's not easy to see. Lots of people here have or know a lot about boats, and are aware of the tides, storms, erosion, marine and bird life. The valley limits the size of fields and the visual landscape - one thinks in terms of hundreds of yards at most, instead of miles. Coming from the east, the town of Stonington is pretty flat until Lord's Hill (the eastern valley ridge), and the shape and texture of the land are more prominent because of that - driving over the hill one becomes aware of the view across the cove, and the sense that one is entering an area set apart. There is a logic to the placement of houses - unlike structures in flat terrain, they're not spread out all over, but are in more constrained areas. One is conscious of what one may see, and how it may have gotten that way.

Nature too is responsive to the shape of the valley - deer run along ridge trails, which lead to various fresh water spots. Foxes, coyote, rabbits, squirrels, raccoons all have established themselves in habitats and spaces that fit their needs, and which reflect a more immediate response to geographic features.

I've always responded to the shape and aesthetics of the world around me, to the point that if I drive through an uncared-for or artificial neighborhood I can feel slightly nauseous. I think this minor curse has also made me aware of some of the above attributes of the valley, and perhaps by assembling these materials using a geographic logic it might help clarify these points.

When I began, I thought this would be a fairly brief web page - but it has grown in a number of interesting directions, far more than I expected. As the span of the effort grew, I became concerned in a different way: was I writing too much about too little? That is, too much detail about places, events, and lives, without a unifying theme to justify the collection? One could imagine, for example, writing about the experiences of all the people whose last name begins with "A" in the state, and while there might be some fascinating anecdotes, it is unlikely that anything edifying would emerge from the work as a whole. It would remain a collection of unconnected elements.

I will leave you, the reader, to judge what the connections might be, as you read on; I have found many. Over the centuries the people here have intermarried to an extent that the ties of blood run almost completely through the area. They largely attended the same few churches and schools. They worked in the same industries: farming, net making, milling, or fishing being the major ones, and weathered droughts, bad crops, and hurricanes together. They helped create the town as a political entity. If anything, the fragmentation that I feared might doom the effort is a modern and recent phenomenon, the result of the suburbanization of a formerly rural area, so that the people who buy new homes here have little or no connection to those who first settled, cleared, farmed, or otherwise developed the land. Even so, I can't believe they are insensitive to the magnificence of a summer morning here, or the crystal clarity of a cold January sky, and though they may not have occasion to think it, I believe they know it is different than it would be in the towns of Mystic or Stonington, Old Mystic or Pawcatuck. It may take more time, but I think the spirit of the place does have an effect.

I will return to address this issue in my concluding remarks, but I should say that it has been one of the more interesting questions I've kept in mind.

Finally, it is relatively easy to find historical information centered on Mystic, Old Mystic, Stonington, or Pawcatuck - but, lacking such a well-known label, the Mistuxet/Quiambaug Valley has been no such magnet for authors, so events, people, and places are usually scattered about in histories of Stonington. I'd like to bring them together.

This is something of a work in progress. Now I know almost all webpage authors say that, but I mean it in a specific way - not that this is a first crude attempt (though if you're reading an early draft that may be so), but rather because, as I've pursued research and talked with people, it's not uncommon to hear "Oh, I have some old photos of that, I'll have to show them to you!", or someone offers information from an unexpected direction. As people read the page(s), I expect they may have material to add, which I heartily encourage - I will publish it and credit it appropriately, or link to it if they wish to make it available directly - and I expect it may substantially extend what is currently here.

I've opted for a pretty much flat-file approach, that is one web page containing everything, with a few minor topics relegated to separate pages. This might be inconvenient for readers who have to wait for the entire page to load - but I expect bandwidth won't be too much of an issue in the future, and the convenience factor weighs heavily towards doing it this way. Structured sets of web pages are great if you're hunting for something specific, but this page is intended to be slowly browsed - who knows what you'll find that intrigues you, and if things were compartmentalized you might never stumble over some of the best things.

I've also tried to reference things as completely as I can. I can't say how frustrating I've found it reading someone assert (in, for instance, a newspaper article from a century ago) that, for instance, some person did something or other in 1680, with no further data about how this is known. Perhaps authors do this so that they must thereafter be used as the source, but the disservice seems out of all proportion to the damage done - this technique short-circuits any attempt to search out further information. As this document is progressing from a series of notes to a more complete text, it is possible that my own sources may not be quite as clear as I would like - don't hesitate to ask.

When I know of a precise location, I give the latitude and longitude to a fairly high precision, in part for those who use GPS. However, this isn't some hyper-finickyness on my part - more importantly, these values have hyperlinks to a KML (Keyhole Markup Language) file, usually ending in ".kmz" meaning that it is a compressed version, which will take you to an overhead view if you have an appropriate viewer installed on your computer, for example the free Google Earth, or Nasa's WorldWind.) As an aside, I suggest that interested readers look into why the term "Keyhole" is used - it derives from spy satellites. One historical work that provides a fairly decent background is "The Wizards of Langley" by Jeffrey T. Richelson.

In part I include reasonably precise coordinates to avoid some of the ambiguity I find in early sources ("That was just south of where Ebenezer Smith's house used to be", with no way to ascertain who or where Ebenezer lived, particularly if there were more than one.) Also, again, the geography is key, and being able to see locations and their relationships with other features is probably the only way to really understand what was going on, or at a minimum to get a rough sense of place.

It may seem a little awkward to use at first. On my computer, which admittedly has fairly high security settings, I'm asked if I want to download the .kmz or .kml file, or to open it, or both; then, when I say "open", I get another dialogue confirming this. Even so, it is worth doing, and you should try it once or twice to become familiar with it. When it finally gets working it's great. I think as the use of these sorts of links becomes more common, the browser integration will be made smoother.

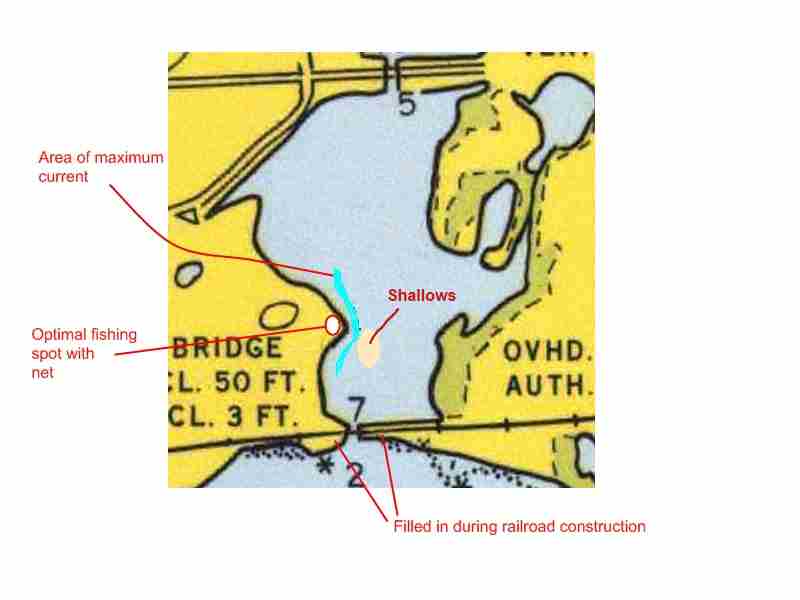

Our local rock is mainly African rock, going back to a time when the tectonic plates were pretty much together. I've put together a separate web page, Connecticut Geology, basically a mirror of a Wesleyan University site, that describes (with illustrations) how we came to be where and how we are. I strongly encourage you to look through it - just contemplating the time scale is a worthwhile mind-stretching exercise.

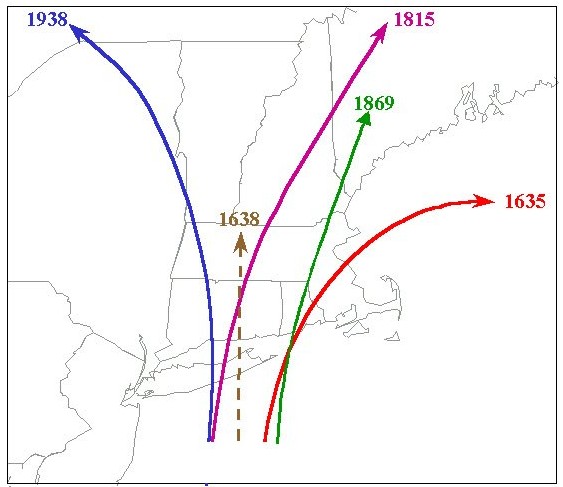

More recently, glaciers have carved the landscape, though the north-south valleys were to some extent already here; the glaciers rounded off hills in places, and when they melted they dropped the stone they were carrying wherever it happened to be. One other large effect of the glaciers (at times having more than a mile of ice thickness) was to plow up great masses of material in front of them. This happened several times; one such push left an east-west running mound (moraine) that became Long Island; a later glacial episode created the North Fork of Long Island, Fisher's Island, Napatree, and that more northerly east-west ridge.

Again from Wesleyan

University's

web

site, , the area of the Quiambaug valley is

Avalonian (Continental) terrane - Proterozoic Z age (600-700? million years old) metamorphosed sedimentary and igneous rocks and Middle Paleozoic age (~370 million years old) metamorphosed igneous rocks.

Gneiss (includes granite gneiss), schist and

quartzite - Hope

Valley belt, Proterozoic Z age.

|

|

A glimpse of the Mystic Grid |

There are also some pockets of Westerly Granite, some of which have been quarried. From the Bedrock Geological Map of Connecticut, you can view the Mystic Quadrangle (well worth the web detour) and see the details; it is interesting that there is a southwest-to-northeast sweep to many of the borders between bedrock types. For those of us who aren't geologists, click here (will open in a new window) for some further information on the above terms.

About 18,000 years ago, Connecticut, the Sound and much of Long Island were covered by a thick sheet of ice, part of the Late Wisconsin Glacier. About 1,000 meters thick in its interior and about 400 to 500 meters thick along its southern edge, it was the most recent of a series of glaciations covering the area over the past 10 million years. Sea level at that time was about 100 meters lower than today.12

The glacier scraped off an average of 20 meters of surface material from the New England landscape, then deposited the sediments, known as drift or terminal moraine, on Long Island, in the Sound and on the Connecticut coast. When the glacier stopped moving for a while 18,000 years ago (as movement of the glacier was in equilibrium with the melting at the southern edge), a large amount of drift was deposited, known as the Ronkonkoma Moraine, which stretches along much of southern Long Island. Later, another period of equilibrium resulted in the Harbor Hill Moraine along most of northern Long Island. The next moraines to the north were created just on and off the Connecticut coast. These moraines, created by much smaller deposits (probably from equilibrium states that were much shorter in time) are discontinuous and much smaller than those to the south (but you'll see them on a chart of Fisher's Island Sound - they'll be the interrupted horizontal (i.e., east-west) deposits, such as the clumps, and Noyes Shoal.)

Sandy plains and beaches resulted from the deposit of drift in these areas, and where the drift cover is thinnest, exposed bedrock creates rocky headlands, often with marshlands behind them.12

Another geological oddity in the area is the set of stones known as "Rocking Stones". In the magazine "Stone", Vol. XI (June to November, 1895), there is an column section entitled "Quiambaug's Rocking Stones". You may find this in the frame below, but it's sensitive enough that you may need to search on "Quiambaug".

These stones are large, and may be rocked slightly, but not tipped over. From the article:

Perhaps the best specimen of the whole lot is the rocking-stone on the land of Miss Moredock. It is about four feet long, two feet wide and three feet high, and it oscillates about five inches, and can be rocked by the pressure of two fingers. It sits on a sloping edge and it looks as if it could be easily rolled off and down the hill, but the combined strength of half a dozen men could not move it out of its place.

It isn't known when humans arrived in this area. After crossing the land bridge from Asia, people did reach the southern tip of South America about 12,000 BC, which is about the time the ice sheets uncovered land in this part of the world. It is possible that there were people living here as early as that time, though the evidence is scanty. The Hidden Creek site (north of the valley about 8 miles) has been carbon-dated to between 10,200 and 9,100 years ago.

What was life like? From an Overview of New England Prehistory:

One of the more classic, often-cited studies is that of Dean Snow (1980:223-232), wherein he presents a model of the Mast Forest Archaic, a widespread cultural adaptation (southern New England and beyond) that began to emerge more than 5,000 years ago in response to the appearance of mature deciduous forest habitats and coastal estuaries. The model is comprised of three critical elements: a settlement pattern of "central-based wandering," a diverse subsistence base founded upon hunting-gathering (or gathering-hunting where shellfish were available) and fishing, and a seasonal round.

4500 years ago, sea level was 33 feet lower than it is today; 1000 years ago, it was about 3 feet lower than it is today13. Connecticut’s climate then was similar to what it is now.

The Narragansetts, a large and well-organized tribe, were in eastern Connecticut and Rhode Island. At some point before the arrival of Europeans, the Pequots (which translated means "invaders" or "destroyers") moved in from somewhere to the north and west, and conquered much of the territory in southeastern Connecticut, possibly splitting the Niantic tribe in the process. Then the ancestors of the Mohegans separated from the Pequots; it is possible that a dispute over a sachem (a political leader similar to a chief) led to hostilities between the two tribes. Thus, their distinct cultures can trace their history back to the some of the same ancestors. The Narragansetts, Mohegans, and Pequots have been separate and distinct nations for hundreds of years, since well before 1609. The last Niantic apparently died in the 1930's.

According to a Siwanoy (or Minnefords) Indian legend, the tribe used warriers, medicine, and magic to chase the devil out of present-day Westchester County; the devil picked up huge boulders lying there and tossed them into Long Island Sound, using them as stepping stones to make his escape. The natives named the rocks "The Devil's Stepping Stones", and Long Island Sound was known as "The Devil's Belt".

The Quiambaug valley was Pequot territory, after the Narragansetts were expelled (which occurred before the first Europeans arrived). At the south of the western ridge was a village; when construction began on the Connecticut Light & Power building in the early 1960's, the land was cleared, and many fire pits were found (this is at latitude 41°20'28.80"N, longitude71°56'23.33"W) . Higher up on the western ridge, not far from running fresh water and several deer paths, a number of artifacts have been found for years, and at the coast to the south are shell middens - piles of discarded clam and scallop shells. This was likely a significant summer settlement. Being on a peninsula, it would have been relatively safe from attack, as well as having fresh water and available food. Even today people search for, and find, arrowheads and other artifacts in the nearby fields.

|

|

A rock hollowed out by grinding by |

A second village was on Wamphassuc point, just south of the Whiting house (latitude 41°20'25.83"N, longitude 71°55'3.45"W). One of the families that lived in that house collected a number of artifacts from that site.

It is known that top of Quoketaug Hill (on the west side of the valley, towards the north - basically just to the east of Old Mystic) was under cultivation by the indians before the colonists arrived. [insert source] From "Houses and Gardens of the New England Indians", by Charles C. Willoughby, 1906, we have this description of what it might have been like - he describes the "three sisters" technique of planting corn, beans, and squash. The general idea is that the corn will provide vertical support for the beans to climb, which the large leaves of the squash shade the ground, keeping weeds down and preventing the earth from drying out in the sun. Typically this planting was done in small hills,

.. The hills were three feet apart, and in each one were placed three or four kernels of corn and as many beans, and the earth heaped up with the shell of the horseshoe crab. Hoes of wood and clam-shell are also recorded, and Williams says stone hoes were formerly used. The Stockbridge Indians employed for this purpose an implement made of the shoulder-blade of a bear, mouse, or deer, fastened to a wooden handle. Sometimes two or three heering or shad (alewives?) were placed in the hill as fertilizer. It was the women's work to plant and cultivate the gardens and gather the crops, "yet sometimes the man himself (either out of love for his Wife or care for his Children, or being an old man)" will assist.

Great care was exercised to keep the ground free from weeds and to protect the young plants from the depredations of birds. As before noted, watch-houses were erected for the latter purpose. Williams says that hawks were kept tame about the cabins to keep small birds from the fields, and although the crows did the corn some injury, not one native in a hundred would kill one because of the tradition that a crow brought them their first grain of corn in one of its ears and a bean in the other from the field of the great god Kautantouwit in the southwest.

The corn (Zea Mays) grown in the gardens of the New England Indians was of several varieties, the colors being red, blue, yellow, and white. The modern improved varieties differ but little from these earlier kinds. The bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) was also of different colors and varieties. Josselyn writes: "They are variegated much, some being bigger a great deal than others; some white, black, red, yellow, blew [sic], spotted." This is the common field and garden bean of the New England farmer.

The pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) and the squash (asqutasquash or isquontersquash; Cucurbita polymorphia were ... [also cultivated]

I had a note from Detective Cody Floyd of the Stonington Police Department about Quoketaug, specifically it's name; he'd been looking into it in the course of genealogical research:

It certainly would be possible that Quoketaug Hill was used as an encampment prior to the attack of the Pequot Fort. Prior to writing this I never had heard of an accurate meaning for the word, Quoketaug. In Rudy’s book he explains that it may mean, “big hill”. I have seen it spelled several different ways on numerous old documents. Some of the different spellings I have seen are, Quaquataug, Quaquetoye, and Quakatuk, Qwaquatack, among others. I contacted Jason R. Mancini who is a Senior Researcher for the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. Jason contacted Jessie “Little Doe” Baird, who is the Director of the Wopanaak (Wampanoag) Language Reclamation Project. Jason asked Jessie my question and she said that this phrase must mean (the inanimate thing) that measures or is used for measurement. She said that it could be spatial too. In other words, it can refer to a place that is used as a reference point on the landscape. She said that there must be something very prominent about the place that was fairly stable and apt to survive over a long period of time. She said that if I was seeing it in deeds especially, she is convinced it refers to a point of geographic reference or a standard by which other things are measured against. Jessie said that she would ideally spell it: qaqátuhak, using the orthographic system she developed for the Pequot Indians. The Wampanoag Language is one of more than three dozen languages classified as belonging to the Algonquian language family. It was the first American Indian language to develop and use an alphabetic writing system. The primary reason for the development of an alphabet was the goal of the missionaries, arriving from England in the early 1600s, to convert the Wampanoag to Christianity. Religious documents began being put to press in the 1640s and the first complete bible printed in the ‘New World’ was published in 1663 in the Wampanoag language. It would not be long before the Wampanoag would use this medium as the principal means of communication with European newcomers throughout New England. The Wampanoag also used the written document to record personal letters, wills, deeds, and land transfers amongst each other and between communities. Wampanoag literacy would rival that of English during the 18th century. The language enjoys the largest corpus of Native written documents on the continent.

An interesting note is that the god Kautantouwit mentioned above was located in the southwest; I have heard that this was because that's the prevailing direction of the warm summer wind. For this reason burials were faced in that direction as well.

|

|

|

The indian languages spoken in this area (Pequot, Mohegan, Narragansett, etc.) were all in the Algonquian (Algic) family. Algonquian is distinct from Algonquin, a specific language in the family. The term "Algonquin" derives from the Maliseet word elakómkwik, "they are our relatives/allies"15. Algonquian languages are apparently descendants of Proto Algonquian, which may have been spoken in the area between Georgian Bay and Lake Ontario, though recently claims have been made that it originated in Montana or Alberta, and has ties to languages in California (Wiyot and Yurok).

Algonquian languages have some interesting features - for instance, nouns have two genders (for lack of a better word), animate and inanimate. Animate nouns are generally used for people, animals, some plants, objects which might contain spirits (e.g. the sun or moon); everything else is inanimate, though sometimes this breakdown isn't as rational as it sounds. Animate nouns have plurals ending in /-ag/, inanimate ones take /-an/ (the vowel may not always be an "a", though.) Nouns may take prefixes and suffixes to indicate possession.

Verbs are central to the languages, and may indicate qualities and aspects of things (essentially replacing adjectives and adverbs). Verbs take prefixes and suffixes based on who is performing the action, whom the action affects, tense, etc. This is one of the more striking features of the languages - longer, virtually compound forms of verb convey a lot of the meaning of a sentence.

In some dialects there is an "obviative" category, which applies to both nouns and verbs. It distinguishes between two third persons in a sentence, e.g., "Sam found Fred". One of these will be considered the main person (called the "proximate", as if nearer the speaker), and the other is secondary and "obviative". This not only may convey some subtlety of meaning, but it helps if word order isn't enforced; for instance, if the previous example where given in this order: "found Fred Sam", the category and the necessary inflections it introduces would clarify the action of the verb.

Verbs may occur in one of several forms, indicating straightforward action, a question (or a subordinate clause), subjective (hypothetical), or participle, as well as in one of several imperative forms. Yes/No questions may be in a special form.

This is just a very brief mention of some of the elements of Algonquian languages (particles are also a key element, for instance); indeed the grammatical richness is likely fully equivalent to what is found in English or other Indo-European languages. I would like to work out as comprehensive grammar and vocabulary of the local Pequot/Mohegan, based upon solid historical sources - but that's another project, one I've had on the back burner for years. If you are interested in the subject, I would recommend as starting places Roger Williams' "A Key Into the Language of America", which concerns itself with the languages he knew from Massachusetts to Rhode Island (though primarily around the Providence, RI area), and also John Eliot's Bible, which he wrote in the Natick dialect (Massachusett and Wampanoag) ; his Indian Grammar is also worthwhile (and has been reprinted from time to time). In both there is the shadow of an underlying idea that perhaps the Indians were descended from the lost tribes of Israel, and similarities in grammar and vocabulary between the local languages and Hebrew were sought for; in light of modern knowledge of migrations and languages this is not at all realistic, so one wonders if it colored these works in any unfortunate way.

The pronunciation of various words is also difficult to be certain of; for example, the colonial transcription problem was as if an American were trying to write down what a Chinese speaker were saying. Not only is the writing system not quite right for the sounds in the language, but the listener hasn't been brought up or trained to hear a number of the phonetic elements (phonemes, tonemes, use of duration, etc.) of the foreign tongue, so no matter how careful in documentation, there will be some error.

When born, the human child can distinguish all of the 600 or so human lingual sounds. In a monolingual home, by the time they are four, they are down to the 50 or 60 used in their language.

One minor advantage we have in this regard is that the Algonquian speakers had contact with the British, French, and Dutch, so we have evidence about pronunciations from writers (and more importantly, listeners) in those three modestly distinct languages. How much of the differences are due to the differing abilities of the listeners, and how much are due to variation in dialect, we may not be able to determine. (For an example of how one would encode the phonetic information, take a look at the International Phonetic Alphabet.; by itself this problem is an interesting subject - it is amazing how wide a variety of sounds human speech has used, such as the Khoisan clicking languages. There have been papers that suggest that the first human languages were clicking languages, but I can find none accessible without subscription to link to - see for instance this Complexity Digest reference.)

I gave a short talk in early 2012 on Indo European and Algonquian, the Indo European part being intended as a more familiar introduction to the kinds of things that might be deduced from a language. A .pdf of the talk is here. It has a bit more detail on the linguistic structure of Algonquian.

From Stonington's Native American Names, by John Hinshaw, the name "Quiambaug"'s origin is:

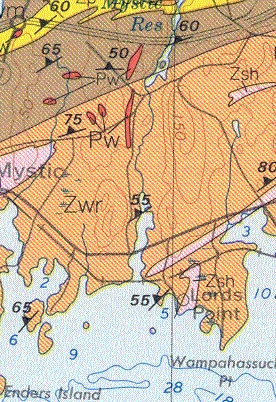

Qui'ambog: "Place to take fish with draw nets." Quanabog or Quaiombog (Manasseh Minor, 1704). Name of cove on Rte 1.

I think this probably referred to a location where large rocks jut out to the deeper, fast current in the lower cove, which would be an excellent place to net fish. This is now between the railroad bridge and the Route 1 bridge, which of course have changed the cove quite a bit.

|

|

The location indicated by the white circle is latitude 41°20'21.76"N, longitude 71°56'15.44"W. |

|

|

| Looking North from the rocky point labeled as 'Optimal fishing spot' on the map above - the site of the original Miner farm is where the house in the photo is. Part of the cove wraps around to the west (left), making this point a bit of a promontory - a great place to fish from. | Looking South from the same

location - the main channel passes right near this point, a few feet to the left. |

from the same source is another place name associated with the valley, at least with its eastern ridge:

Waumphas'suc or Wamphas'set: "Swamps, marsh, bog or wet meadows." Neck of land on the west side of Stonington Harbor.

Finally, the northern brook that ran down through what is now the reservoir in the northern part of the valley was known as the Mistuxet Brook:

Mistucksuck: "Mistick brook" or "At little Mistick." A brook about two miles east of Mystic River, running to the head of Quiambaug Cove.

Unfortunately, "Quiambaug" is not the most melodious of names - perhaps nothing suggestive of "bog" is. I don't like this place because of its name, but it would seem a shame to change it after a few hundred years. I have one naming convention I sometimes use, which I sort of stumbled upon growing up on Cove Road. Our house there is at the base of the western ridge, and looks across the cove to the eastern ridge - and when the sun comes up in the morning, that eastern ridge is dark and in shadow, while the western ridge is all aglow with golden early morning light. I just called our ridge the "morning ridge", and, as the same effect occurs in reverse in the evening, the eastern ridge became the "evening ridge" (in a few older sources, this is known as "Palmer Hill"). This is the sort of thing that is really obvious if you're here, but might not be if you're not used to north-south valleys. I may use these terms elsewhere in this page, as writing "the eastern ridge of the Quiambaug Valley" gets a little tiresome, both for writer and reader.

There have been a few names for the valley, and/or the stream that flows into it from the North. The current name of the stream is Copp's Brook, but as above was originally known as Mistuxet Brook; indeed when Thomas Minor moved to the area he "moved to Mistuxet" (Wheeler, pg. ). I've also found references to it as "Caulkin's Brook", notably in a paper by Richard C. Wheeler, which he read to the Westerly Business Men's Association on January 21, 1886, entitled "Historical Sketch of Stonington & Westerly". This is why I've changed the title from "Quiambaug Valley" to "Quiambaug/Mistuxet Valley".

|

|

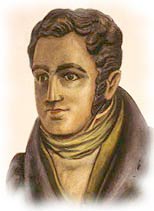

Giovanni Verrazano |

There were sporadic contacts between Europeans and Indians in New England in the 16th Century, though the documentation is sparse.

In 1524 the Florentine explorerGiovanni da Verrazzano explored the east coast in the ship La Dauphine, entering New York harbor.

Sailing further east, Verrazano and his

men then

encountered Block Island and Narragansett Bay. The local Wampanoag

people (New

England Algonquians) were also friendly, welcoming them with food and

escorting

La Dauphine to the more sheltered Newport Harbor. Here, the ship

anchored for

two weeks, where the crew traded with the Wampanoag while awaiting

better

weather.6

It's hard to believe he wouldn't have looked in a bit at the eastern end of Long Island while sailing to Block Island.

|

|

Bartholomew Gosnold |

Exploring the Gulf of Maine in 1602, Bartholomew Gosnold (who later named Cape Cod, and remained for a time on Cuttyhunk Island) met Indians who used leather square sails in their canoes, which could be raised and lowered as those on square-rigged European sailing ships. Gosnold found the people living there were already using European goods. John Brereton, a member of Bartholomew Gosnold's 1602 expedition to the Maine coast reported:

"...six Indians in a baske shallop with a mast and saile, an iron grapple, and a kettle of copper [who] came boldly aboard us, one of them apparrelled with a waistcoat and breeches of black serge, made after our sea fashion, hose and shoes on his feet... from some words and signs they made [we concluded] that some baske or [other vessel] of St. John do Luz [had] fished or traded in this place."5

It could be that the Indians had traded with the Basque fishermen (who spent time on the Grand Banks) for their goods, or had interacted with Europeans settling in the St. Lawrence Valley - which had been explored as early as 1499. It is possible that the occasional shipwreck introduced Europeans to Indians as well. Or it could have been some mixture of these reasons. Gosnold was a prominent figure in the establishment of Jamestown, Virginia, where he died; his grave may now have been found.

Some of the Europeans who visited New England in the 16th century had heard tales of a great Indian city and region called Norumbega, and some of the early explorers searched here for the mythical city of that name. This involved interacting with the tribes as much as exploring the coastline.

I think that this fragmentary history disguises an important point:

by the

time serious settlers arrived in New England, the Indians had had

experiences

with Europeans for perhaps 100 years or so - and this experience was

that

Europeans visited in small numbers, perhaps traded a bit, and then

left.

As more Europeans gradually entered the area, the nature of the

settlement going

on probably seemed like more of the same sort of interaction, not as

the

beginning of an influx of permanent settlers.

In 1614, Adriaen Block made his fourth voyage to the lower Hudson in the Tyger, accompanied by several other ships equipped for trading. While moored near southern Manhattan, the Tyger was accidentally destroyed by fire.

In 1916, workmen uncovered the prow and keel of the Tyger excavating a new station for the New York City subway near the intersection of Greenwich and Dey streets - the area having been since filled in with landfill). Portions of the ship were removed and are preserved in the Museum of the City of New York. The remainder of the ship still rests approximately 20 feet (6 m) below ground, due east of the former site of the North Tower of the World Trade Center.)

|

|

The Tyger |

|

|

A model of the Onrust |

Over the winter, he and his men, possibly with help from the Lenape Indians, built the 42-foot 16-ton ship, the Onrust (meaning Trouble, or Restless).

From the History of the City of New York:

In this Block explored the East River and was the first European to navigate the Hellegat (now "Hell Gate") to enter Long Island Sound. He visited the Housatonic River and the Connecticut River, which he traveled at least as far as present-day Hartford, sixty miles upstream. He then went on to chart Block Island and Narragansett Bay; he may be the one who named the area "Roode Eylandt" after the red (Dutch roode) color of its soil. He met one of the other expedition ships at Cape Cod, and left the Onrust behind before returning to Europe. (New Netherland Routes, Inc., a non profit organization in Schenectady, NY, is currently building a replica of the Onrust using authentic 17th Century Dutch ship building techniques, recently rediscovered by the organization's master shipwright.) As of now it looks like they've succeeded:

|

|

Onrust replica docked in Manhattan |

In the course of this trip he did explore Fisher's Island, which he named "Vischer's Island" after his first mate. That island was called "Munnawtawkit" by the Pequots, possibly meaning "planting fields" - a name which also seems to be the root of "Montauk". Coming around to the north side of the island, where the harbors are, would have put him within sight of the (relatively large) extended mouth of Quiambaug Cove, the bay from Dodges and Andrews islands to the fingers of Lord's Point. This map by Block shows that he was inshore enough to round Sandy Point and explore the Pawcatuck River - so it is likely that he was the first European to visit the area.

| The red points illustrate the general sweep of the coast

that creates a welcoming and quite large apparent bay at the mouth of Quiambaug Cove. While it's noticeable on the map above, it is even more striking when approaching from the water. |

He may have even spent a little time in the valley - it is one of the more convenient places to acquire fresh water. One could do that at the head of the Mystic River, but that's quite a ways inland, and shallow enough that much of the trip would have to have been by small boat; or possibly at the northwestern part of Stonington Harbor, coming in along Wamphassuc Point to where Sylvia's Pond drains in via Quanaduck - but this is much less obvious a location when viewed from the water. The Quiambaug Valley sort of draws one in with a large apparent bay, leading in to a promising north/south tidal cove - at the head of which is fresh water. It'd be great if some archaeological evidence turned up as to the early visitors who might have watered there, but it is very unlikely.

A map based upon Block's chart was published by Willem Janszoon Blaeu, entitled "Nova Belgica et Anglia Nova", in 1935; you may view it here (394 KB) . It covers the coast from Virginia up to New France; if you look closely, you can see Fisher's Island, and the distinctive hook of Sandy Point; the Quiambaug Valley appears on it distinctly as a green valley to the left of the word "Poqusio o", which word I can't make out clearly. The easiest way to find it on the map is to identify the Thames River (one river "down" from the Connecticut River), then find the Mystic River (which has a notation I can't make out; possibly in part "Sicanemus" the Indian name for the Mystic River10, page 5), and then move further down to the Quiambaug Valley. Below that is Stonington Harbor, pretty much in line with Sandy Point.

The Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center has a re-creation of a 16th century coastal Pequot village - it's probably very much like what the life at the Quiambaug summer village was like in both the 16th and 17th centuries, if you ignore the Potemkin Village aspects of their reconstruction.

In 1605 Captain George Waymouth of England observed indians whaling off of Massachusetts and/or further north, saying:

One special thing is their manner of killing the whale ... they go in company of their kings with a multitide of their boats, and strike him with a bone made in fashion of a harping iron fastened to a rope... then all their boats come about him, and as he risith above the water, with their arrows they shoot him to death"

Manasseh Minor records whaling in the area, with boats being damaged by whales, and "whale at wadawanuk" on the 10th of March, 1702/3. The amount of meat and fat provided by a single whale must have been a major boon to the indians.

|

| Click on the picture for more information on the Pequot Village reconstruction |

From about 1620 onwards the Pequots were involved in trade with Europeans (primarily the Dutch and English), involving both fur and wampum. The Dutch began settling as far east as the Connecticut River, and there seems to have been a bit of contention between the Dutch and English over both territory and trade.

A smallpox epidemic in 1633/1634 killed thousands of Indians in southern New England.

The Pequot War (1636-1638) vastly diminished the Pequot tribe's strength and influence. The origins and conduct of the war are too substantial to go into here; a good summary may be found in Wikipedia's entry on it or www.pequotwar.com. One of the key events was the attack and destruction of the Pequot fort in Mystic (about 2 miles west of the Quiambaug valley) by John Mason on May 26, 1637. Surviving members of the tribe later scattered, some joining other indigenous settlements. A remnant continued to live in Connecticut.

Not long after these events, settlers began to arrive in the area. One of them was Thomas Minor, who is considered one of the four founders of the Town of Stonington. In 1653 he bought the land in the Quiambaug from Cary Latham of New London. He lived in his house there (latitude 41°20'33.11"N, longitude 71°56'15.83"W ) with his wife Grace Palmer, along with 6 sons and 1 daughter: John, age 16, Clement, age 14, Thomas Jr., age 12, Ephraim, age 10, Josiah, age 8, Manasseh, age 5, and Ann, age 3.3

He had intended to live in Wequetequock, where he moved to in 1652 and built a house on the east side of the cove. At about this time Walter Palmer bought 300 acres of land on the east side of the cove from Governor Haynes, and this was found to include Thomas Minor's house. They arrived at an agreement - Palmer moved into Minor's house, and Minor built his new house in Quiambaug. If it hadn't been for the mixup over ownership of the land, the Quiambaug Valley might not have been settled for some time.

From the Stonington Historical Society's web page about the founders of Stonington (one of whom was Thomas Minor):

Thomas Minor was born in 1608 in Chew Magna, Somersetshire, the son of Clement Minor. As a young man he sailed on the Lyons Whelp and landed at Salem. After several moves he settled in Charlestown, where he became a founding member of the First Church in 1632. He married Grace Palmer, daughter of Walter Palmer, and they soon moved to Hingham, where they raised five children. After 14 years in Massachusetts the family joined John Winthrop, Jr., in the settlement of Pequot (New London) in 1646. There he held important offices, most for several terms: assistant magistrate, sergeant in the New London Train Band, New London deputy to the Connecticut Court, and judge.

The diary of Thomas Minor is a lasting memorial. Although the entries are terse and never give details, they do give us a glimpse into his daily life and community activities. He records many births, marriages, and deaths among his neighbors. He meticulously records the day of the week, the number of days in the month and the year, for no doubt this served as his only calendar. He entered the date when a field was planted and its yield, for this would guide him in his planting the following year; unusual weather conditions such as "a great snow" or "bitter cold" made his diary truly his farmer's almanac. The death of his 21-year-old son is reported in simple and unemotional language, though it must have caused him considerable pain. He makes brief notes of some of his financial transactions. It is a great treasure.

He was elected Stonington deputy to the General

Court four

times, town clerk twice, and selectman nine times. He was often asked

to

participate in Indian negotiations and was constantly required to lay

out

boundaries for land grants. In his diary he wrote:

The 24th of Aprill, 1669, I Thomas Minor am by my accounts sixtie one yeares ould I was by the towne and this year Chosen to be a select man the Townes Treasurer The Townes Recorder The brander of horses by the General Courte Recorded the head officer of the Traine band by the same Courte one the ffoure that have the charge of the milishcia of the whole Countie and Chosen and the sworne Commissioner and one to assist in keeping the Countie Courte.

He was the chief military officer and in 1676, when King Philip's War started, Lieutenant Thomas Minor, then 68 years old, picked up his musket and marched off to battle accompanied by several of his sons.

Minor lived in Stonington thirty-eight years, much longer than any other early settler, dying in 1690 at the age of 83. Two hundred years after his death Grace Wheeler visited the site of the Minor homestead and found a little hollow in the ground, a few old stone steps, and a row of lilacs which could have been planted by Thomas himself. Those lilacs would be a fitting memorial for a man who dearly loved his orchard and his plantings.

(There is another house in roughly the same location now, at the corner of Cove Rd. and Route 1).

He likely was a Puritan, as John Winthrop was, as well as his fellow settlers in New London. He must have been a tough old bird to march of to war when nearly 70.

Perhaps the only source of information about the Quiambaug Valley in the 1600's is the Diary of Thomas Minor. From the introduction to the 1899 edition (reprinted in 1993), pages 3, 4:

The Diary has been handed down through successive generations remaining on the old Thomas Minor homestead property at Quiambaug, in the town of Stonington...

The writer of the Diary, Thomas Minor, came from Somersett County, England, on the good ship Arabella [a matter of dispute - Ed.], which landed at Salem, Massachusetts, the 14th day of June, 1630. He sterling qualities placed him in the position to at once become a prominent figure in the affairs of the Colony...

But it is after he has determined to settle permanently at "Quiambaug", on lands which he has acquired partly by grant, because of valuable services with the Indians, during the year 1653 or 1654 that he takes up the Diary and carries it on faithfully till July 26, 1684.

To give you a flavor of the diary, here is an entry for 1654 (spelling, punctuation as in the original):

The first month is march .1654 and hath .31 days wensday the first friday the third John went to Coneticut & tusday the .7. I made an End of hewing of timber at the mill brooke watch came backe from Coneticut and wensday the eight I begun to plow the wheat land and monday the .13. I made an End of sowing pasnepes and monday the .22. I looked for the swine and wensday .29. I vewed Cary lathams farm and friday .31

The above entry represents one month. It is somewhat difficult to track in detail what is happening in the diary - places aren't identified in a recoverable way, and it is in many ways a listing of agricultural highlights, with occasional visitors or other events mentioned. It does give some picture of local life in places, though; for instance:, from pages 8-9:

Sabiantwosucke promised the .30. of desember befor mr stanton and tomus shaw to make Watch a canoow for that which I had and to bring me six pecks of nunup (Indian word for beans).

Some extended quotes may be found here, which provides a listing of entries for one year. There is an interesting analysis of his diary in "By Nature and by Custom Cursed: Transatlantic Civil Discourse and New England Cultural Production, 1620-1660", by Phillip H. Round, Tufts University, starting on page 99. If this link is still valid, you may find this here. One thing I found a little surprising in the diary was the prickly nature of the relationships between the settlers; at some points they were suing each other over matters, at others supporting each other in various ways, or cooperating in politics.

From a Carol Kimball article "The mysterious Indian conspiracy of 1669 started with rumors":

..Disquieting rumors of a supposed Indian uprising led by Ninigret, the sachem of the Rhode Island Nehantics, worried the settlers in eastern Connecticut. Friends in Rhode Island and others from Montauk on Long Island warned them there was trouble in the air...

Apparently the unrest began in 1669 in early winter at Robin's Fort Hill in Groton, when Robin Cassasinamon, the Pequot sachem, held a great dance in the Indian fashion. Guests included Uncas, sachem of the Mohegans, and Ningret, with their followers.

Cassasinamon had explained that the indians intended to do no harm to the English, but Thomas Stanton showed up and demanded Ninigret. Cassasinamon paid Stanton a great deal (20 lbs) of wampum to leave.

... but in late spring and summer the rumors began. One Thomas Edwards testified before Thomas Minor of Stonington and James Avery of Groton that Ningret was about to build three wigwams to host a great meeting of local Indians, including those from Block Island, the Pequots, Mohegans, Wampanoags, and Mohawks, "and they were minded to fight."

The colonists made preparations; one of them was

.. at a Stonington town meeting held on Jlu 9, it was voted that "Thomas Minor shall receive all the arms and ammunition that Quaquatage Indians do or shall bring to his house." He was to keep them until the Town saw fit to restore them to the Indians. ... Minor later reported that he collected 18 guns from various Indians along with powder horns and bags, but "no pistols".

No report of Capt. Wait Winthrop's session with Ninigret has yet been found, but their meeting must have been successful, for the feared uprising never took place. In fact, a few years later, the Connecticut Indians became strong allies of the English during King Philip's War in 1676.

(At the end of that war the Narragansett chief Canonchet was taken prisoner, brought to Anguilla in Stonington, and executed.)

Thomas fought in the Indian wars in 1675 and 1676, (being a "lieutenant or captain" in King Philip's War) when he was 68 years old; he continued to farm into his 76th year. From an article by James Cortese,, he was a Puritan, and a book about the Miner family states that "he was a friend of John Winthrop Jr., and joined Winthrop's colony of Puritans in the settlement of New London.

On October 22, 1667 Thomas Minor set off driving a mixed herd of cattle via Narragansett and Providence to Boston. They spent a night at "Wilxon's near the lead mine," where a thunderstorm killed 3 pigs. At this time by order of the General Court all Stonington cattle were branded with the letter "K", as there was much trouble with rustlers.

According to a Carol Kimball article, one of his descendants was William C. Minor, the madman of "The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary", by Simon Winchester (Harper Collins 1998). This Minor was a resident of the Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane.

William had been born on the island now known as Sri Lanka, the son of missionaries from New England. At age 14 he was sent back to the US, and he finished his education as a surgeon at Yale University in 1863. At this point he joined the Union Army as a surgeon and served at the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864. One of his duties was to punish runaway soldiers by branding them with a "D" for "deserter". At the end of the war Minor had duty in New York City, and spent a lot of time with prostitutes. This behavior earned him a transfer to the Florida Panhandle; by 1868 his mental state was such that he was in a lunatic asylum in Washington, DC.

In 1871 he moved to the slum of Lambeth in London, where he fatally shot George Merrett, whom he'd thought had broken into his room. He was tried and found not guilty by reason of insanity, and sent to Broadmoor. He wasn't considered dangerous, and could acquire books. Upon hearing of the need for volunteers, he devoted much of his remaining life to systematically working through his library and compiling lists of words and their frequencies. The editor of the OED visited him and they became friends.

He returned to the US, and was diagnoses with schizophrenia. He died in 1920 in New Haven.

|

|

The Denison Homestead, now a museum, on the site of the "grate manor house" at Pequotsepos |

In 1654 Captain George Denison moved from New London to "a lean-to surrounded by a palisade at Pequotsepos, bringing his wife, Ann Borodell, and his children, Sarah, age 13; Hannah, 11; (daughters of his first wife); John, 8; Ann, 5; Borodell, 3; and the infant George Jr."3. While much of his land may be said to be in the Pequotsepos valley, his later house is certainly on the east side of that, and thereby is within our area of interest. About the same time he was fined 24s. for selling rum to one of his Indian friends. Also in 1654 "A pyne neck by the broad cove" (Lord's Point) was granted to Isaac Willey, who sold it within the year to Amos Richardson. Wampassock (550 acres) was granted to Hugh Caulkins, who later sold it to John Winthrop, Jr.

On October 15, George Denison took a petition by horseback to the Governor and Magistrates of Massachusetts "that you would please to accupt us under your Government & grant unto us the liberty and priveledges of a Townshipp.", as Connecticut was balking at allowing the creation of an independent town. He was warmly welcomed, not only because he'd fought with Cromwell in the English Revolution, but he was also the brother of the husband of Gov. Dudley's daughter, and Massachusetts was eager to expand its claims. On October 21, Massachusetts made formal claim at Hartford to the land east of the (now) Thames River.

On June 30 the population of Stonington drew up a sort of "Declaration of Independence" ("History of the First Congregational Church, Stonington, Conn., 1674-1874, by Richard Anson Wheeler, page 32, available at books.google.com):

|

Asotiation of Poquatuck Peple: Whereas thear is a difference between the 2 Collonyes of the Matachusetts and Conecticoate about the government of this plac, whearby we are deprived of Expectation of protection from either, but in ways of Curecy, & whereas we had a command from the generall Court of the Matachusetts to order our own business in peac with common consent till further provition be made for us, in obedyience to which commuand we have addresses or selvs thearunto, but cannot atain it in regard of soomm distractions among ourselves, and thear hath bene injurious isolencys done unto soom persons, - the cattell of others threatened to be taken away, - and the chattell of soom others already taiken away by violent. We haveing taken into consideration that in tymes so full of danger as theas are, unyon of our harts and percons is most conducing to the publick tood & safety of the place - thearfore in pursuance of the same, the better to confirm a mutual confydence in one another & that we may be perservedin righteousness and peac with such as do commenc with us, & that misdemeanors may be corrected and incorrygable persons punished: - We hose names are hereunto subscribed to hearby promis, testify & declare to maintain and deffend with our persons and estait the peac of the plac and to aid and assist one another acoarding to law & rules of righteousnessacoarding to the true intent & meaning of our association tull such other provition be maide ffor us as may atain our end above written, whereunto we willingly give our assent, & nether ffor ffear, hoape or other respects shall ever relinquish this promis till other provition be maide ffor us. And we do not this out of anny disrespec unto either of the aforesaid governments which we are bound ever to honnor, but in the vacancy of any other aforesaid. George Denison Moses Palmer Thomas Shaw Walter Palmer Nathaniel Chesebrough Tho. Stanton Elihu Palmer Willm Chesebrough Thomas Stanton Samuel Chesebrough Elisha Chesebrough

|

George Denison and William Chesebrough were elected commissioners to conduct the affairs of the town. So, for a brief time in 1654, the area was in word and deed independent, led by George Denison. However, in October Massachusetts accepted the area as a town ("Southertown"), and George "ruled with a high hand"3, pg. 14, granting lands to friends without any respect for Connecticut deeds - 800 acres was even deeded to Harvard College (I have no information if this included any land in the Quiambaug valley, though that seems likely). This was all nullified in 1662 when John Winthrop, as agent for Connecticut, received a new charter setting the Pawcatuck River as the eastern boundary of Connecticut, restoring Stonington to its current state. George Denison never seemed to quite give up - in 1664 he was brought into court for marrying a couple under his Massachusetts commission.

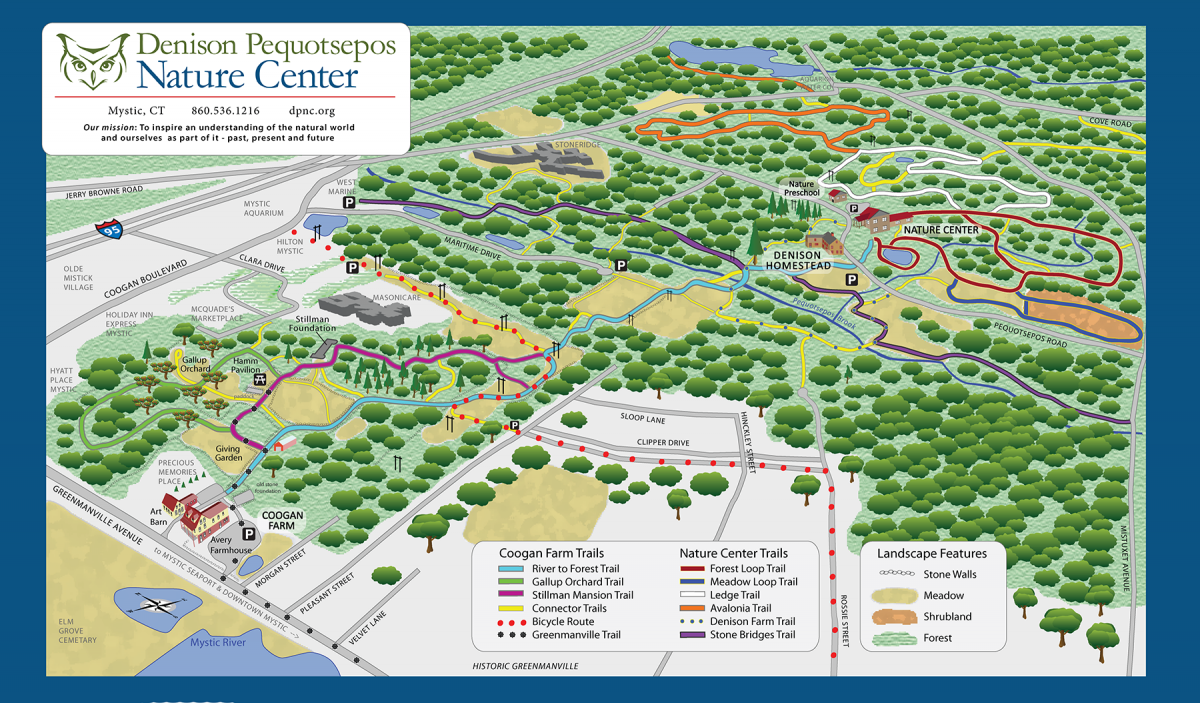

In 1663 George Denison built his "grate manor house" at Pequotsepos (latitude 41°21'47.29"N, longitude 71°56'51.08"W). His grandson would build a grander house on the same site, after the earlier structure burned to the ground. This newer house still stands - it is a museum, operated by the Denison Society. You may even take a virtual tour.

From the Genealogy of Will & Sandi Pearson web page :

The authorities in Connecticut welcomed back all the inhabitants except Captain Denison. He had been the ringleader in Massachusetts, so they not only refused him civil rights but fined him £20 for “illegally” performing marriages. These odious distinctions made the Captain boiling mad. He refused to pay the fine and brazenly performed two marriages, one of them of his own daughter. They then raised his fine to £100, a vast sum in those days. The Captain was an important figure, with many friends, and accordingly after two years the Connecticut General Court remitted its un-collectable fine, and forgave him.

...Almost continuously he was elected to represent [Stonington] at the General Court, until the second session of 1694 during which he died on active duty in Hartford and was buried there. In his will, written on January 24, 1693/94, the land was given to his children and grandchildren, thus it split up much of the homestead. The old home called Pequotsepos Manor burned in 1717 on the eve of the wedding of George Denison 3rd , the grandson who had inherited it and the adjoining 200 acres of the original land grant. He rebuilt west of the original site, salvaging some of the big charred oak beams from the frame of the older building.

George Denison died in Hartford on October 23, 1694, and was buried there.

|

|

|

"Hear lies the

body of Captain George |

The grave of his wife is in Elm Grove Cemetery, where it was moved from near the homestead (#48, Oliver Denison cemetery).

|

|

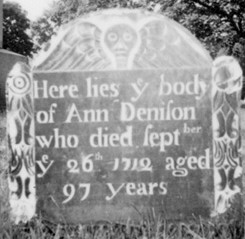

"Here lies y body of Ann Denison |

A note on "ye"; no one ever really said "ye". The "y" was a printer's shorthand for the old English rune "thorn", þ, that wasn't in the imported German or Italian typefaces (if you imagine dropping the lower right half of the circle, thorn looks very much like a distorted "y".. Thorn is pronounced as "th", so "ye" should be read as "the". A bit more on this topic is available at Wikipedia's entry for thorn.

|

| An 18th century painting of Captain William Kidd |

William "Captain" Kidd (c.1645 – May 23, 1701) is remembered for his trial and execution for piracy; his privateering career had often bordered on piracy, and at times he crossed the line. He might have gotten away with it 50 years earlier, when the law was less rigorously enforced, and trade concerns had not risen in prominence. From "Under the Black Flag"2:

Kidd was a victim of circumstance, but he was also the victim of defects in his character. He seems to have had some of the same traits as Captain Bligh of the Bounty. He was a good seaman, but he had a violent temper and a fatal inability to earn the respect of his crew. Unlike Bligh, who was a small man, Kidd was large and powerful and bullied his men. He was constantly engaged in arguments and quarrels. A local agent who met him at the Indian port of Carwar described him as a 'very lusty man, fighting with his men on any occasion, often calling for his pistols and threatening any one that durst speak anything contrary to his mind to knock out their braines, causing them to dread him...' He annoyed dockworkers and sea captains by his arrogant manner and his habit of boasting about his grand connections. He deluded himself about his motives and his actions when he turned pirate in the Indian Ocean, and no doubt deserved the biting comment which was made by a Member of Parliament at the time of his trial: 'I thought him only a knave. I now know him to be a fool as well.' [page 180]

He was also one of the few pirates known to have actually buried treasure.

He had a wife, Sarah Oort, a wealthy widow whom he'd married on May 16, 1691, and two daughters who lived in New York [in a house on Pearl St. built by one of my ancestors - Ed.]. He arrived back in New York in 1699, after pretty much all of his exploits, to see them after an absence of three years. He began negotiations with his former supporter Lord Bellomont (Richard Coote, the Royal Governor of both New England and New York) in Boston to try to get some sort of pardon. During this time, Captain Kidd moved his ship to the eastern end of Long Island Sound, moving from Block Island to Gardiner's Island to the Connecticut coast. At some point during these two months, three sloops came alongside to take off some of Kidd's crew with their belongings and share of the booty. Kidd sent Lady Bellomont an enameled box with four jewels in it; also Mrs. Kidd sent a six-pound bag of pieces of eight to Thomas Way, and Kidd sent several pounds of gold, believed to be worth £10,000, to Major Selleck in Connecticut. He also buried a significant amount of treasure, mainly from the Quedah Merchant, on Gardiner's Island. (ibid, pg. 190)

His career ended with his arrest in Boston on July 6, 1699. After his transfer to England, Lord Bellomont made strenuous efforts to locate and retrieve the treasure. In the end 1,111 ounces of gold, 2,353 ounces of silver, forty-one bales of goods, bags of silver pieces, and various jewels were recovered (As listed in Bellomont's summary), representing a value of £14,000 - nothing like the £40,000 Kidd had led Bellomont to expect, and a tiny fraction of the £400,000 Kidd was rumored to have plundered in the Indian Ocean. The auction of this treasure raised £6,472, to found the Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich. So there is quite possibly some unlocated treasure.

What does this have to do with the Valley, at least with my extended definition of it? According to my Stonington High School classmate Nathan Leonard, who grew up on Wamphassuc Point, treasure hunters have been nosing around that area for years. John Hallam owned much of Lamberts Grove (cove now), and was reputedly one of Captain Kidd's fences, selling material he provided to merchants in Boston. He may have buried some materials near his house that were 'in transit' to sales elsewhere, or, as a somewhat trusted partner, may have been relied on to safeguard it.

From Nathan Leonard:

John Hallam, owned most of Lamberts Grove (Cove now). There are a few Hallam graves from the 1700s in the grave yard on Wamphassuc Pt (go to rail road crossing, park on either side; walk East along tracks toward Borough, when you are running out of land on the North side there is a grave yard. Be prepared for some wicked poison ivy). There are some more gravestones missing, sadly. I recall a couple earlier Hallam graves that I don't see now. A few have eroded into the cove. Hallam house is on Collins Rd. Going north from Rte 1, go over little bridge/hump in the road that is fun to jump motorcycles off and another few hundred yard on right is an old gambrel roof house as I recall (not the barn home north of it which might have been a later addition to their farm. John Hallam was not liked in Stonington in the end. He supposedly brought back some nasty disease like small pox or influenza from Boston. He survived but many in the area did not.

John Hallam was born in 1661 or 1662 in Barbados, and died on November 20, 1700, at age 39. He came to Stonington in 1676 or 1677 from Barbados when he was 16, with his younger brother Nicholas16, page 411, his mother Alice, who died in 1698, and his stepfather John Liveen of New London, CT, where they lived, until he came to Stonington about 1680.

There were a number of Hallams in Barbados, and I expect there was some connection through there that formed the basis of Hallam & Kidd's acquaintanceship.

John married Prudence (b. 1661 in Boston, daughter of Amos Richardson) on March 15, 1683. After he died, she would marry Elnathan Miner; she died in 1716, and is buried in the Thomas Miner cemetery.9 I would think that if anyone knew anything about treasure buried locally it would have been John's wife, but as far as I can ascertain nothing notable turned up in later years.

| Captain John Hallam's house | A close-up of the sign | A view of the cove, now mostly marsh, below the house |

From the Stonington Chronology, pg. 28, in 1699:

Captain John Hallam, who lived at Wamphasset Pt. west of Stonington Harbor, gave a bond to the Governor and Council to make restoration to the colony for having stored goods stolen by the pirate, Capt. Kidd, and for harboring two of his men.

also, on the same page for November 5, 1700:

Capt. John Hallam returned from Boston, bringing with him the smallpox so that during the succeeding months he, himself and many others in Stonington, both Indians and whites, died of this disease.

which indeed would not have made him a popular person. Another source has a slight variant of this, but the import is in substance the same.

Wheeler's "History of Stonington"16, page 411 has a bit more about John Hallam:

Mr. Hallam [after his wedding - Ed.] at once engaged in the mercantile business, which was the employment of his stepfather, in the West Indies, and at New London, after they had taken up their residence there. Mr. Hallam enlarged his business here and opened commercial relations with merchants at Barbadoes, which he very successfully prosecuted for several years.

There was a problem with his mother's will - she had said her estate was to go to her two children, but Liveen gave it to the ministry of New London. This caused a legal controversy both here and in England; the appeal of the children did not succeed.

Mr. Hallam, in prosecuting his commercial relations with Barbadoes and the West Indies, acted as super-cargo of the vessels conveying his goods to these islands, and in person superintended the sale thereof, and exchange of the same for goods of the islands, which he brought home and sold to the merchants in this region round about. During the year 1700 Mr. Hallam purchased and fitted out one of his vessels with the products of neighboring farms and went with the same to the West Indies as super-cargo. Somewhere on his return he caught the smallpox, with which he died Nov. 20, 1700.

Mr. Hallam, after his marriage with Miss Prudence Richardson, purchased a large and valuable tract of land of her brother, the Rev. John Richardson, whose father, Mr. Amos Richardson, had given him as a wedding present, on his marriage. The land embraced in said purchase, included the land lying between Stonington Harbor, Lambert's Cove and Stony Brook on the east, Fisher's Island Sound on the south and Quiambaug Cove on the west up to a point, from which a direct line easterly passing about thirty rods south of the residence of Mr. Henry M. Palmer to Stony Brook, constituted the north boundary line of said tract of land.

According to Grace Wheeler's book, the John Hallam house is the oldest house in Stonington. The Stanton/Davis house (now museum) in Pawcatuck may have been built earlier; apparently it was built circa 1670 by Thomas Stanton.

From Caulkin's History of New London, concerning Amos Richardson; the boldface items (mine) highlight elements of the local geography or interest - e.g., as mentioned above, the 'pyne neck' is Lord's Point:

He also obtained a number of grants of land, very

early in

settlement at Pequot. The New London town records show the following:

"Memorandum for town meeting Sept. 20, 1651, Amos Richardson is to have

a

lot." Caulkin's History states that he was from Boston and had

commercial

dealings with the planters and that instead of taking up a new lot he

purchased

that of Richard Post on Post Hill. "Aug. 9, 1653. House lot to Amos

Richardson brother, the millwright (afterwards called

brother-in-law)." "He had subsequently a grant of a large farm

east of the river under the same vague denomination: he has not been

identified."

"Two necks of land extending into the Sound, one

called 'a pyne neck,' with a broad cove between them, was granted

to Isaac

Willey and by him sold to Amos Richardson." "Still another containing

several hundred acres of land and separated from Hugh Caulkin's land by

a brook

called Mistuxet, was laid out to Amos Richardson and his brother in

1653."1* Part of this division was known by the Indian name of

"Quonaduck."

In October, 1661, Antipas Newman, of Wenham, sold

him a large

tract of land, called Caulkin's Neck, bounded by the above Quonaduck

farm on the

East, Caulkin's brook West, Capt. George Denison's North, and South by

the Sea.

Pequot, now New London, embraced the present town of Stonington, where

the last

three of the above described grants were located.

The deed of the Indian sachem Nealewort for a part

of this

land was dated August 26, 1658, and is recorded at Stonington. It is

described

as "a tract of land called Quinabogue lying and being near to the

country

of the Late Pequed Indians for and in consideration of the great Love

and

affection I beare unto Amos Richardson of Boston in the Mass. Colony,

Englishman. * * * contain by measure one English mile and half square

on each

side of that River called Quinabogue River next Adjoining to ye land or

farme

granted to John Winthrop Esq. Governor of the English Colony on

Connecticut

River northward of the said farme and is called by the name of

Nayumscut and

Quaduecatuck."

Wheeler's "History of Stonington" locates this

property as "the land lying between Stonington Harbor, Lambert's Cove

and

Stony Brook on the east, Fisher's Island Sound on the south, and Quiambaug

Cove

on

the

west

up to a point, from which a direct line easterly

passing

about thirty rods south of the residence of Mr. Henry M. Palmer to

Stony Brook,

constituted the north boundary line of said tract of land."

The family name of Mary, wife of Amos Richardson, is

unknown;

he did not, however, have a second wife, as stated in the "Richardson

Memorial." It is probable that they were married in 1642, the year that

be

purchased his house and garden. It is conjectured that the

brother-in-law

referred to above was Richard Smith, of Lancaster, a "mill-wright,"

whose first wife Mary died with her infant March 27, 1654, and who

married, on

the 10th of the following August, Joanna Quarles at Boston. It is quite

certain

that John and Mary Smith, who are claimed to have been the parents of

Richard

were not the parents of Amos Richardson's wife.

They had a daughter Alice, however, who probably

became

second wife of John Tinker, a man very closely associated Amos

Richardson.

He named one of his sons Amos and the inventory of

John

estate2 shows that a farm of 240 acres and other property had been

deeded to Mr.

Richardson for the use of John, Mary and Amos, children of John

Tinker.

In 1656 the eight proprietors of Groton included

this Richard

Smith, with Dean Winthrop, John Tinker and Amos Richardson. Soon after

this he

moved to Lyme, Conn., where he was a deputy in 1678-9.

His children were Richard (probably by his first

wife), John,

born 1655, Francis, 1657, James, Elizabeth, who married John Lee. He

had a

grandson named Quarles Smith, and the Lyme records mention two Roland

grandsons.

Mary Smith died in 1659 and her husband in July 1669. In May prior to his death John Smith gave all of his estate to son-in- law, John Moore, in consideration for his support; his will mentions only four children - John, Richard, Ann and Alice. There were -so many John and Richard Smiths that it if; very difficult to untangle their history. The Diary of Thomas Minor, of Stonington, refers to Amos Richardson and his family more than eighty times. On October 29, 1660, he says, "carried the firkin of butter to Mr. Smith's for Amos." November 2, 1660, "I weighed Amos his firkin of butter at Mr. Smith's." The following receipt for a horse delivered in the presence of Thomas Minor, Jr., and Ephriam Minor is also found in the Diary: "Delivered unto poor man mine (torn) A horse that he bout of a mister Richinsoone and by his appointment and order a horse a chestnut Culer with a blase in his face." * * * "I Say by mee delivered this 14 day of aguste 1661 with my hand Richard Smith." Mr. Richardson at this time lived in Boston.

From Wheeler's "History of Stonington"16, page 18: